The Quality of The VIX Close's 1D-Ahead Volatility Forecast Across Different Assets

How good a forecast is the VIX Close's 1d-ahead volatility prediction? In other words, if the VIX closes at a certain value, what does that say about tomorrows volatility?

For those interested in getting into quant stuff, I’ll be recommending useful resources each time and occasionally giving what I think is helpful advice. For today, here is a very useful R book. It will help you learn how to pre-process finance data in R and build some useful commonly used models.

I wanted to know if the VIX’s close is indicative of the next day’s intraday volatility. I say VIX but I really mean vol index. I’ll use the terms interchangeably.

To answer this, we can turn the VIX’s close into a daily vol figure and use it as a 1d-ahead vol forecast, then, compare it with the next day’s intraday volatility by using the mean absolute deviation (MAD) or the mean-squared error (MSE) to quantify the deviation between the forecast and the realized vol.

Easy enough, but there’s a problem: Intraday data is expensive and hard to find. Is there a way to estimate intraday volatility from daily data? Luckily there is. We can use the formula given by Parkinson (1980) which was shown by Chan and Lien (2003) to be a coherent risk measure. The formula is:

That a risk measure is coherent is very important. Coherent risk measures satisfy four mathematical properties outlined by Artzner et al (1999) that ensure that risk measures are consistent with probability theory and are mathematically sound. The propeties are monotonicity, sub-additivity, positive homogeneity and translation invariance. Don’t be thrown off by the mathematical jargon—they are actually simple concepts.

Monotonicity means that one asset’s returns (X) are consistently higher than another (Y), then it should be considered riskier. Or:

Sub-additivity means that the risk of a combination of assets should be less than their individual risk. Or:

Value-at-risk (VaR) doesn’t satisfy this property! If you measure your risk using VaR, then the risk of your diversified portfolio can be higher than the sum of the risks of the different assets; which means that when shit hits the fans, you will lose more than you were prepared to. That’s why after the financial crisis of ‘08, a lot of onlookers and academics argued that VaR should be replaced as the de jure risk measure. They mainly argued that It’s better to use expected shortfall, aka Conditional VaR (CVaR), although some are still unsatisfied with this alternative. A good reason to make the switch, which is also due to sub-additivity, is that VaR is notoriously difficult to optimize numerically. You will keep running into local minimas if you use a numerical algorithm like Nelder-Mead. CVaR is coherent and easy to optimize.

Positive Homogeneity means that if you scale an assets return by a constant, then you should be able to scale the risk by the same factor, or:

Translation invariance is similar but swap an additive constant for a multiplicative one.

The four properties combine to make sure a risk measure is reliable and can be used to diversify. Good thing then that our chosen intraday vol measure satisfies these properties.

One property it doesn’t satisfy is unbiasedness. If you really want an unbiased intraday vol measure that you can calculate from daily data, you can use this one by Garman and Klass(1980). It uses open and close prices too. I prefer the former simpler one.

After calculating the intraday vols, I checked how much they deviated from the VIX-implied range. The chart isn’t pretty, but here it is.

We see that the difference between the VIX’s implied intraday vol and the realized intraday vol is usually sub-1%, but in times of turmoil, it is a lot. Remember that the MAD measures deviations on both sides, positive and negative. All it shows is how big the offset is.

We have seen in a recent post that the VIX generally overestimates volatility in normal times and underestimates it during downturns. You can read it here:

This is similar but not exactly the same. One the one hand, the VIX-implied volatility and realized volatility are often correlated. If one increases, so does the other. That is similar to what we saw in the previous post. Here are some charts of the 21-day correlation between the VIX-implied range and the next day’s intraday vol that show just how much each vol index overestimates the underlying’s intraday vol.

But, that they increase and decrease at similar times doesn’t say anything about which one exceeds the other. For that we need to look at their difference charts:

You can see that the VIX overestimates realized vol by about 1% more or less, but when the intraday volatility breaches the VIX-implied levels, the difference can be yuge!

The proportion of times when the VIX-Implied range is higher than the next day range for various assets is shown below. Positive means the VIX’s implied range was higher and negative means it was lower.

So the two ranges are positively correlated, but the VIX-implied range overestimates the next day’s range by about 1% about 50-77% of the time depending on the asset, and when it underestimates the next day’s range, it is by a lot. Does that mean that you can take a contrarian trade if the VIX-implied range is breached?

One problem with this idea is that the VIX’s implied range is breached too often. What’s more rare is for the close to be above or below the VIX-implied range boundaries. Here is a table of that.

So about 6-17% of the time the close is above or below the VIX-implied upper or lower bound. From here I made a contrarian strategy that went the other direction if the VIX closed above or below the upper or lower VIX-implied bounds. The chart below shows the cumulative returns of the strategy for individual assets.

The white line are the SPY’s cumulative returns. When the strategy was applied to AAPL, GOOG, QQQ and AMZN it beat the SPY, but SPY, DIA, GLD, IBM, and EEM didn’t. Only EEM finished with negative returns over the entire period.

Interestingly, the cumulative returns of the overall strategy show that it stopped working overall after COVID despite it working for some assets since then. I think that’s because in times of turmoil, realized vol is higher than implied vol so taking a contrarian view, which in this case would be a long position, would lead to losses.

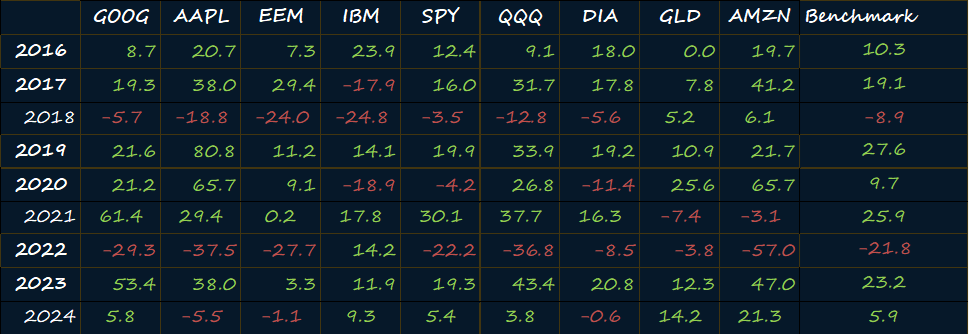

For a more granular look, here are the CAGR and annualized vol tables of the strategy vs the benchmark (SPY).

The strategy’s worst year was 2022 followed by 2018. It often outperforms the benchmark too.

But it is a lot more volatile than the benchmark. I highlighted periods when it was less volatile. Only in DIA and GLD do you have less annualized vol, but that’s because both of these assets are typically less volatile than the SPY and not because of the strategy.

So we’ve learnt that the changes in the VIX close can tell you whether the next day’s intraday vol will increase or decrease, but it isn’t gospel. The correlation is high enough and often positive, but it turns negative too from time to time. As for the VIX-implied ranges, we’ve seen that the next-day’s range often breaches these levels quite often, but it is not often that we close on the wrong side of those bounds. And if you take the contrarian view you can make alpha for certain assets.

That’s it for now.

Interesting findings Lago. I don't have much knowledge of VIX Vols and not much of a mathematical background but I can see what you are trying to discover, and I am learning along the way, so thanks.

Keep it up, your posts are well written and detailed.